On the morning of Easter Monday, Sybille and I set off from Brno, to spend the first few days of my post-Easter break, exploring some more parts of the Czech Republic we have not previously visited. We drove about 40 km north from Brno, to the town of Boskovice. Despite seeing ever-increasing amounts of snow lying on the surrounding countryside as we drove into the hills of the Moravský kras, the main roads were fortunately perfectly clear.

We parked the ‘Carly’ in the somewhat snow-covered Masarykovo námestí, the main square in the town centre, which is dominated at the west end, by the impressive Kostel Sv. Jakuba Staršího/Church of St. James the Great. From there, we set out to discover two of Boskovice’s main landmarks. A large Zámek/Chateau, which dates from the early nineteenth century and is built on the site of a former Dominican monastery.

And the quite substantial ruined remains of a 13th century castle. Unfortunately, despite a sign indicating that the castle would be open because it was Easter Monday – a public holiday, we discovered at the end of our walk up a snow-covered hill, that it was closed. We suspect that this was due to the adverse weather conditions. This was a shame as I understand that there are excellent views from the castle, across the surrounding countryside.

For several centuries, there was a large Jewish population living in Boskovice. The Jewish quarter of the town, is among the best preserved monuments of Jewish culture in the whole of the Czech Republic. In 1942, during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, 458 Jewish men, women and children, were deported from Boskovice, initially to Terezín, and then on to concentration camps such as Auschwitz. Of those deported, only fourteen survived.

The main synagogue was built in 1639 and was altered and extended over the following centuries. During the eighteenth century, the interior walls were decorated with frescos, the work of Polish Jewish artists. Having been neglected and used as a warehouse during the Communist era, following the Velvet Revolution, restoration work began with the synagogue being reopened to the public in 2002. Whilst many of the frescos at lower levels have been lost, no doubt due to rising damp, those at higher levels around the ladies gallery, are remarkably intact.

Having seen a note on the door of the synagogue during the morning of Easter Monday, that it would be open from 13.00 that afternoon, we returned there after a late lunch at 14.50. We were greeted by the lady in charge who fortunately spoke fluent German. She explained that the synagogue had again been closed for several months over the past winter in order for further restoration work to be undertaken. Monday 1st April was reopening day and we were the first visitors of 2013. I duly christened the 2013 page of the visitors book!

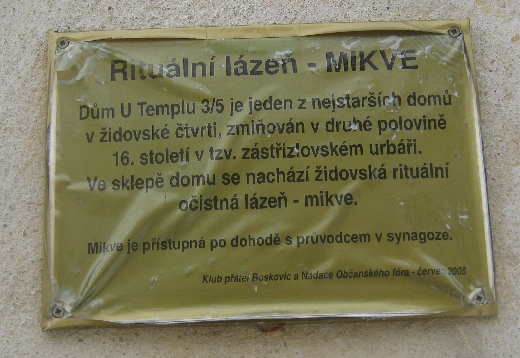

As well as the synagogue, the lady in charge also took us across the road to the basement of a house, where there is a restored private mikve for Jewish ritual washing. This mikve is a relatively recent find, following the ownership of the house changing hands. The new owner decided to clear out the rubbish & rubble from the basement of his house, and made this remarkable discovery!

At the south-western end of Boskovice, there is the third largest Jewish cemetery in the whole of the Czech Republic, containing around 2500 headstones. As in this example, inscriptions are usually in both Hebrew and German.

Boskovice does not even rate a mention in our ‘Lonely Planet Guide to the the Czech Republic and Slovakia’. Fortunately, I had come across a couple of snippets of information about the town elsewhere, which is what prompted our visit. Seeing the amazing artwork in the restored synagogue and private mikve, were the highlights of an informative and fascinating day.