One of the complications of the Czech language, is that nouns have different endings according to their gender and the case being used. As consequence, nearly all Czech females, have a surname that is slightly different from, and longer than, the surname of their father or husband, from which it is derived. In most cases, this occurs by the addition of ‘ová’ onto the end of the male surname.

The obvious example to illustrate this point, is the now-retired, famous Czech tennis player Martina Navrátilová. Martina’s step-father, who married her mother when she was six, is Miroslav Navrátil. She took his name and thus is Martina Navrátilová. There are some exceptions to this rule, which arise when the male surname ends in a vowel. Sticking with Czech tennis players, the country’s current best female player is Petra Kvitová. Her father is Jirí Kvita. The ‘a’ on the end of his surname is dropped and the ‘ová’ is added.

The grammatical reason for this change is it being in the genitive case. And what does the genitive case indicate? Possession! Effectively it is saying that the Czech woman is the possession of the man, either her father or husband. It is an interesting concept for any Czech woman who thinks of herself as being a feminist 🙂

Whilst it is not my place to question the grammatical rules of the Czech language, what I do find absurd and inappropriate, is applying these same rules to the surnames of women who are not Czech. What really brought this to my attention was in November 2010, when the engagement of Prince William to Kate Middleton was announced. As far as the Czech media were concerned, both television and newspapers, Prince William was now engaged to a lady called Kate Middletonová. I am sorry folks, but a lady with the name Kate Middletonová, does not exist.

A more recent example I came across, was when watching a live broadcast of the London Olympics on my computer last summer. CT4, Czech TV’s sports channel, was broadcasting the games, using the coverage provided by the BBC. It was the final of a sprint race for women. Almost exclusively, the competitors were black Africans or ladies from the Caribbean. As these competitors got down on their blocks, the BBC pictures showed captions with their wonderfully different names and the countries they were representing. But the Czech commentator still told his audience what the name was of each competitor, adding ‘ová’ to each and every one of them. It was utterly absurd.

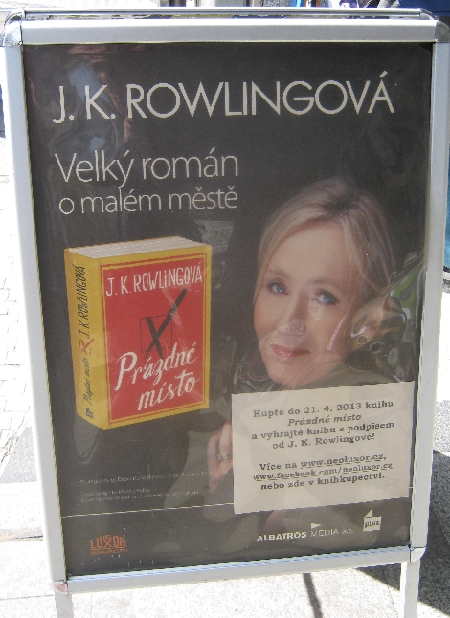

My photograph illustrates very clearly, the point I am making. It shows an advertising poster for the Czech translation of the recently published adult novel, entitled in English as, ‘The Casual Vacancy’, by the author of the Harry Potter stories, J. K. Rowling. But as you can see, the Czech publisher feels obliged to tell you that it is actually written by a British author who appears to be drunk as she is J. K. Rowlingová – ‘J. K. Rolling over’ 🙂 .

But change is slowly coming – both at an official and unofficial level. A change in the law some years ago, does now mean that a non-Czech woman, who marries a Czech man, is no longer required to put ‘ová’ onto the end of her new surname. Thus there are two American ladies in the St. Clement’s congregation who are married to Czech men, who have the surnames, ‘Novak’ and ‘Vacik’, rather than ‘Novaková’ and ‘Vaciková’. Unlike in the UK or the USA, as part of the legal preliminaries to a Czech wedding, the couple have to declare what surnames they will use following their marriage, and must sign their Marriage Protokol during the marriage ceremony, using those agreed names.

Also unofficially, a number of Czech publishers are now publishing books by non-Czech female authors, translated from English and other non-Slavic languages, into Czech, without altering the author’s surname. Likewise, posters for Hollywood films being shown here, either with subtitles, or more commonly dubbed, are increasingly not featuring those unknown actresses, Jennifer Anistonová and Cameron Diazová, but featuring Jennifer Aniston and Cameron Diaz.

I am sure this change will not please some Czech language purists but in my opinion, it makes perfect sense. After all, when writing in English about the latest tennis match played by Petra Kvitová, no one would dream of calling her Petra Kvita.

And don’t let’s forget about the time honoured English-speaking tradition of renaming the wife as Mrs Husband’s First Name Husband’s Family Name … Which makes me, very occasionally, Mrs Ricky Yates. SY

Sybille – As you well know, I dislike this practice as much as you do 🙁

Well, I beg to differ. I know this feature of the Czech languages stupefies foreigners, but this is how Czech – a highly inflected language – works. We simply need those endings to decline words and to build sentences properly. Similarly, the Baltic languages need to add an -s to foreign names. When I saw the jersey of a Czech football player playing for a Lithuanian team, it certainly look funny and awkward – but I accept is as a given and do not take issue with it.

As a translator, I encounter this problem frequently. My decision always depends on the nature of the document and the intended audience. In corporate communication, I may leave Paula Smith’s name intact in addresses and organizational charts (basically where the name is likely to be in the nominative case), but probably not in a newsletter article on her achievements where her name will probably appear in various grammar cases (unless the client explicitly requests otherwise, which happens from time to time – I always have to grit my teeth in silent fury). In fiction, I would not even consider dropping -ová. Accordingly, “with Paula Smith” would be “s Paulou Smithovou”. The advocates of original names would probably go with “s Paulou Smith”. But you could say that a lady called “Paulou Smith” does not exist, couldn’t you? I am sorry but my tongue would probably fall off if I tried to say “s Paula Smith”. In your example with female athletes from the Caribbean, the discrepancy between the written form on the screen and what the commentator actually said is not surprising. As we say, “paper withstands anything”, but when you try to say it aloud, it gets really awkward.

By the way, it has nothing to do with the genitive case. If the man’s surname is Novák, the genitive is Nováka, while his wife is called Nováková. You probably mean the possessive form (Novákova), which is similar to the female name but not always (e.g. male name: Novotný, possesive: Novotného, his wife: Novotná).

I am a woman myself, and I do not perceive our Czech endings as sexist. If anything is discriminatory about names, it is the very concept of women taking their husbands’ names after marriage (I’m not necessarily saying I would abolish this practice). In this respect, your culture is as guilty as mine.

This “feminism gone mad” leads to peculiar situations: In case of an expression like “Angela Merkel as a special guest”, formerly we would automatically say “Angela Merkelová jako zvláštní host”. Nowadays, feminists would have us say “Angela Merkel jako zvláštní hostka”, i.e. dropping the feminine ending of her name but creating a neologism of the word “guest” (like “guestess”), which has a single form for both genders. Give me a break…

Hi Jana,

Thank you for visiting & for leaving this long & thoughtful comment with your most helpful explanation of the issues you face as a translator. Whilst not in any way disagreeing with what you say, I did discuss this whole issue with a female Czech, who also works as a translator, before compiling this post. It was she who confirmed to me that the addition of ‘ová’ was the genitive case & implied possession by the male. However, you are perfectly right in pointing out that in the English-speaking world, the norm is for a woman who marries a man, to take on her husband’s surname. The only difference is that we don’t add additional suffixes!

To stay on the topic of Baltic names: Czech media add the Czech female ending to Lithuanian or Latvian surnames that already have female endings. The result is often very convoluted sounding even in Czech (because they end in vowels, and those are usually left there in this case) – and frankly, quite wrong. Redundant.

But even though I often roll my eyes at foreign names changed thus, I agree that this is simply how Czech works, and it is difficult to get rid of it if we do not want to sound odd. Our language is highly genderised, which I mean in a completely grammatical sense – even objects have grammatic genders.

It’s difficult to explain this to English speakers, I guess – in a way, it is similar to the way English sentences require a subject, no matter what. We say simply “prší” in Czech; you must say “it rains”, although there is actually no “it”. Does that make sense?

And Ricky, there are some surnames that do not require this ending – those ending with -í or -u (with the little ring above)! There are not many surnames like that, but there are some nonetheless.

Thank you Hana, for your contribution to this debate.

Regarding your first paragraph, a similar thing occasionally happens when an English word which is already plural, is adopted into Czech. The most obvious example is ‘chips’ (American English for what I would call ‘crisps’), which in Czech becomes ‘chipsy’ 🙂

I do understand the highly genderised nature of Czech which this post has highlighted. But equally, I too roll my eyes at ‘Kate Middletonová’ or ‘Margaret Thatcherová’ as ladies with these names do not exist!

And yes – I was aware that some surnames don’t require the ‘ová’ suffix as I did write, ‘in most cases’, not ‘in all cases’. I know a man whose surname is ‘Rovny’ whose mother is ‘Rovna’ and also knew that the odd surname ending in ‘u’ kroužek doesn’t change at all.

I love language debates.

I noticed another thing – there are ladies who “get away” with their names. Namely, the singer Tonya Graves, who’s been living in the Czech Republic for years and years now, and must have come at the time when this -ová change was even more universally accepted. Nobody calles her Tonya Gravesová, and I think it’s a proof that this really is as much a grammatical issue as one of cultural perceptions. Her first name, you see, can be inflected the usual Czech way, so we get over her unusual for us surname. None of the other ladies you listed have names that easily transfer into Czech, first names as well as surnames.

So as a best-selling author in translation I’d be Lis Sowerbuttsova ? Can’t happen – won’t fit on the cover! It doesn’t make any sense at all – we have a Russian dancing couple in NZ – his surname is Mullayanov, her’s is Mullayanova – and that is how they are called in English – even though as they are brother and sister in English we should “fix” it to Mullayanov for both!

I think it’s far more difficult for names that are transliterated from a different alphabet – but in a Latin alphabet language I’ll think I’ll keep my name as is. Seems like another good reason not to have a publisher to market your books as an author !

Yes Lis, if you were to allow a Czech publisher to publish any of your self-published books, translated into Czech, officially you would be the best-selling author Lis Sowerbuttsová – btw you do need the diacritic over the ‘a’ at the end. It would indeed need a big cover 🙂

The example you give of the Russian brother & sister living in NZ, is another example of what I am describing as I understand that this is a linguistic trait of Slavic languages. It isn’t a result of Russian being written with the Cyrillic alphabet. The one saving grace of Czech is that it uses the Latin alphabet, but it still is apparently, the most complicated of all the Slavic languages.

I am a female and a feminist and someone who did not change her name when she got married. I love my name. It was chosen with love my parents. I love honoring that. Anyone who has ever been a parent knows how much thought and love went into that selection. Why would a man or a nation not honor that by calling me by the name I have had my entire life?

Your post is so important Ricky, and highlights a much-needed reform with excellent research. Modern thoughts require modern language. Without it, how likely is modern thought to occur?

Thank you Karen – I don’t think I have the right to tell the Czech people to change the grammatical rules of their language – all I was doing was pointing out the possessive meaning of the genitive case and its implications. A number of young Czech women have made this point to me. What I do think is absurd is the insistence of adding ‘ová’ to the surname of a non-Czech female. It is both misleading and inconsiderate in my opinion. For example, your ‘First Lady’ is not Michelle Obamová!

Regarding genitive: Your translator friend must have meant the English possessive, sometimes called the Saxon genitive. -ová really does not have anything to do with the genitive case in Czech.

By the way, if you say “Jana’s opinion”, aren’t you disrespecting my name? I’m not Jana’s, after all. 🙂 Where’s the difference between -ová and -‘s? Both are appended directly to the name. In both cases because the complex fabric of the respective language requires it.

Jana – My translator friend said in conversation, which I then checked back with her via email, that the addition of ‘ová’ was the genitive case and indicated possession. And she then remarked about the implication of that, as have one or two other Czech women I’ve spoken to on the subject. Only today in a discussion about this post on Facebook, which I would much prefer to have here as a comment, an English man who has been married to a Czech lady for a number of years, says that his wife regards the ‘ová’ on the end of her surname, as meaning ‘belonging to her husband’.

Regarding your second paragraph, in the normal correct written form of English which I was taught many, many years ago in school 🙂 , you would write ‘the opinion of Jana’. ‘Jana’s opinion’ is the commonly used spoken form though, as language changes, is now deemed to be an acceptable written form too! But at least the ending is not different according to gender 🙂

Jana, thank you very much for the complex, thoughtful and very accurate reasoning of your position on this matter (which fully agrees with mine). I think it is most important that people “from the outside” who come across “the -ová problem” understand that it has nothing to do with disrespect either to the feminine sex, or to the original language of the “ová-ised” name.

I know that many people hate putting the -ová to the foreign female surnames, exactly because there was never, for example, a British Prime Minister who called herself Margaret Thatcherová. But this logic, if applied consistently, would also forbid us to inflect foreign names at all, male of female, as rightly reminded by Jana.

Unfortunately (from my point of view), there are many Czechs who forget or neglect the fact that this issue is linguistic rather than ideological and passionately condemn the addition of -ová to foreign names. However, based on my personal experience, even the people who carefully use the “non-ová-ed” surnames while mentioning public figures will routinely slip into using the suffix in further conversation, especially while inflecting, precisely because the Czech language tends to avoid indeclinable nouns and -ová is the default way how to make them capable of inflection.

PS: Ricky, you close your answer “at least the ending is not different according to gender”. Why would that be a bad thing? Different does in no way mean less worthy!

Gosh what a fascinating post and discussion. I’m totally unqualified to add to it, other than to say that in Jana’s last comment, the difference is that in English, the ‘s is just added temporarily in a particular context, rather than as a permanent suffix. Given the immense grammatical complexity of Czech I do see her point in her detailed first comment.

Turning to the topic of a woman taking her husband’s name on marriage, in France a woman legally retains her maiden name throughout life on all formal documents. We found this out when our French cottage was purchased in my name only and we discovered that it was my maiden name which appeared in the legal contracts and was registered with the relevant authorities. It felt very odd, I can tell you. 🙂

Yes Perpetua- I had a feeling that this post, which I’ve been mindful to write for some time, was likely to provoke some interesting discussion 🙂 Thank you for your response on the ‘s issue. It is just added temporarily in a particular context, rather than as a permanent suffix.

Like you, I do think the long detailed first comment by Jana is very well argued & I acknowledged that in my first response. There are two sides to the argument regarding adding ‘ová’ to the surname of a non-Czech female. One view is that adding a Czech female suffix to a foreign surname means deliberately changing a woman’s name and is therefore both misleading and inconsiderate and that is the view I take, as sometimes, as in the Olympic Games commentary I described, it borders on the absurd. But there is the traditionalist view that only by adding the suffix, can the name be used as a flexible feminine adjective within a naturally sounding Czech sentence, which is what Jana is effectively arguing.

Regarding a woman changing her surname upon marriage, I never knew that about the situation in France. As I explained in my post, here in the Czech Republic, the couple agree whilst completing their legal preliminaries before the marriage ceremony, what names they will use & confirm this when they sign their Marriage Protokol. In Germany, as part of the legally required civil ceremony in the Rathaus, the couple declare what name(s) they will use in the future which then officially changes their legally registered name(s) recorded somewhere in Berlin 😉 Because Sybille & I were married under the law of England & Wales and had therefore not made such declarations, we had a wonderfully bureaucratic performance to get Sybille a new German passport as Sybille Yates, some eighteen months after our wedding when her previous passport in her maiden name expired.

I can well imagine the complications, Ricky. In France, women do take their husband’s surname in everyday life. It’s just that as a legal entity a woman is always known by her maiden name (with her married name in brackets, so to speak). I’ve managed to get all the French authorities and utilities to send me communications in my married name, but it took quite some effort with one or two of them. 🙂

I could probably write a very long blog post about all we had to do just to change Sybille’s registered name in Berlin before she could then apply for a new passport in her married name. We had to appear before a young female civil servant at the German Embassy in London with a pile of papers three centimetres thick consisting of an original & two photocopies of every document imaginable in relation to the two of us that you could ever think of. There was a period of six months between the expiry of her old passport & the German authorities finally agreeing to issue her a new one as Sybille Yates, during which time she couldn’t leave the UK because she had no valid form of ID. German & Czech bureaucracy have a large amount in common I’m afraid 🙁

Ricky, I have a few words to say about this blog but I’ll save them for later.

However, after you spent a long while discussing the names of two terrific tennis players and Katya Middletonova, you wrote:

“Almost exclusively, the competitors were black Africans or ladies from the Caribbean. As these competitors got down on their blocks, the BBC pictures showed captions with their wonderfully different names and the countries they were representing.”

To reveal the absurdity you should have mentioned names such as the delightful Shelly-Ann Prycerova-Fraserova (she’s delightful, her name in its original form or in Czech is a bit of a mouthful) or Camilla Jeterova or even Veronica Campbellova-Brownova. However, not all the ladies were “black Africans” or from the Caribbean. Three were from the USA.

David – I couldn’t remember which race it was – 100m, 200m or 400m. It was a sprint race because they were using blocks. But the names you offer sound familiar & illustrate the absurdity of what I was describing. Depending on which final it was, I’m sure you are also right in saying that there were American competitors too.

Hi Ricky,

The results of a male/female, non-representative straw poll (i.e. among my students) suggests the following:

– When pressed, some people do have the vague idea (expertly dismissed by Jana) that the ová somehow indicates possession.

– None of the women have considered removing the ová from their surnames, but they don’t see why other women shouldn’t do so if they wish to.

– There is a degree of sympathy for foreign women who don’t like having ová added to their original surname.

– However, when asked to say simple phrases in Czech without the ová (with Ms Rowling/Novák, without Ms Rowling/Novák, from Ms Rowling/Novák, etc.) they started giggling and recognised the impracticality of any changes.

– Interestingly, the one issue that came up again and again was the positive benefit of the ová rule. In e-mail correspondence with English speakers, people here are often unaware whether they are addressing a man or woman (what to make of a mail signed by e.g. Kim Johnson?) while the same goes for newspaper headlines such as “Clinton flies into Prague” (Hillary or Bill?).

Perhaps gender-poor English should think of a suitable suffix and introduce it at the earliest possible moment…

Jonathan

Many thanks for this comment Jonathan, in particular for leaving it here as well as on Facebook. I will try & get Katka to do the same as you will see from her FB comment, she very much takes a different view when it comes to adding ‘ová’ to end of the surname of ladies who are not Czech.

Whilst I take the point that having ‘ová’ on the end of a surname in an email, does clearly indicate the gender of the person writing, Czech can also be very gender confusing when it changes male names into their female form, no doubt once more due to the case and the gender of the noun. For example, Jan Palach Square in Prague is Námestí Jana Palacha. In my first wedding of 2012 in which Petr (male Czech) married Kristen (female American), when asking ‘Kristin, will you take Petr to be your husband?’ in Czech it becomes, ‘Kristin, bereš si Petra za svého manžela?’. In both examples, the Czech male names Jan & Petr, become the Czech female names Jana & Petra 😉

“Whilst I take the point that having ‘ová’ on the end of a surname in an email, does clearly indicate the gender of the person writing, Czech can also be very gender confusing when it changes male names into their female form, no doubt once more due to the case and the gender of the noun. For example, Jan Palach Square in Prague is Námestí Jana Palacha.”

Ricky, ová on the end of the surname is also useful in the world of academia. Imagine writing a review of Professor Novak’s book and using masculine pronouns throughout only to find that Professor Novak is a woman. I use this example since a Czech emigree’s family in Canada may follow Canadian convention and not ova-ise the surname. This point was made today to me by a Professor at the University where I teach a class.

In your example of Jan Palach Square, Jana Palacha is not a feminine form. It’s the second case of the names Jan and Palacha (which you rightly identify as being masculine). Just because it looks as though it’s feminine doesn’t mean it is. Of course, had Jan Palach married a woman called Jana, she would have been Jana Palachová. And the square would be Námestí Jany Palachové.

David – Thank you for your explanation of why the male Czech name takes the female form in the first example I cited. But it doesn’t take away from the confusion that it causes to anyone who doesn’t have an understanding of Czech grammar.

As advised by Ricky, I am pasting my comment previously posted on FB…

I must say (and I’m certainly not the only one) that I absolutely DETEST the adding of -ová to the surnames of women who do not have anything to do with the Czech Republic at all, do not live here, are not married to a Czech or whatever. Yet, I’m afraid the only thing that would make the stubborn / arrogant Czech grammar moguls change their stance would be some major and well publicized lawsuit at the European court of wherever by some film megastar or other similar important and well-known person, protesting against having her surname distorted into an unwanted form.

Thanks Katka, for transferring your comment here from FB, as it puts the alternative view to that of Jana in her earlier comments. I for one, strongly agree with you 🙂

The name thing is odd for me too. I know people who have elected to not use the ‘-ová’ suffix but they are married to foreigners. And of course there is a fee for this.

http://chrisinbrnocr.blogspot.com/2012/11/czech-names.html

Christopher – I think it seems odd to everyone who isn’t Czech 🙂 As I say in my post, the law was changed some years ago, giving the right to a foreign woman who marries a Czech man, not to put ‘ová’ on the end of her married surname. And I believe the reverse is also true. As I understand it, the fee involved is no different to the fee paid for completing legal preliminaries before the marriage takes place for, as I also explained in my post, that is where you declare what names are to be used following the wedding & the names in which both bride & groom sign when completing their Marriage Protokol during their wedding ceremony.

Further to my previous comment in the defence of -ová, I have one more thought on the same topic. I do not agree with the notion that changing the original form of the name is something which must be automatically condemned.

It is important to remember, that by adjusting the form of any name to the laws of the “host language”, we are not denying its holder of its original name. this changed form is meant solely for the inner need of the speakers of the target language, who will still fully and safely recognise the identity of the person mentioned.

Let me give you an example from another language: if I remember it correctly, a Japanese speaker would render my first name, in speech and in writing, as Maruchinu (or similar, apologies to any Japanese who might read this if I made a mistake), simply because “Martin” is unpronounceable in their language. I can think of no reason in the world why I should be offended by the fact that I am called Maruchinu even though this does not appear on my birth certificate. For a Japanese speaker, that would be the clearest, most straightforward reference which would neatly serve its purpose with reasonable level of accuracy while still sounding adequately familiar to a local ear.

In this context, I can think of on one Jewish religious principle that is stated in the Talmud: “Let the rule of the country be the rule” 🙂

PS: Katko, this is not a matter of language purism, neither is it a law rigidly applied from the above by an anonymous mass of “grammar moguls”. I am very observant about this matter and whilst not a language expert, at least from my personal experience I can say that an average Czech native speaker irrespective of age or sex will find it most natural to use the suffixed version.

Hello again, for the third and I promise last time (I don’t seem able to stop today, do I? 🙂 )

I just remembered a little story that happened to my sister (who by the way is a decisively anti foreign-ová person) 10 years ago. She happened to work as a volunteer at an international theatre festival in Hradec Králové and as a fluent French speaker, she was asked to be a guide and interpretor for the French actress Annie Girardot. When my sister asked her for an autograph, Madame Girardot insisted on signing her name “Annie Girardotová”, citing her appreciative amusement by our -ová rule which she found clever.

PS: After looking at the picture with the poster of J. K. Rowling’s book carefully, I, too, was horrified by an act of linguistic barbarity. Rather than the fatal suffix, however, it was the little white note in the bottom right corner what gave me goosebumps. It encourages the customers to get an early copy “s podpisem OD J. K. Rowlingové” (“with J. K. Rowling’s signature”). The preposition od, of course, is redundant, the genitive case (which would be impossible to express without the suffix) is abundantly sufficient. Personally, I find the lack of respect to these little grammatical nuances far more worrying than the “feminisation” of foreign surnames.

Martin – thank you for all three of your comments which I’ve just managed to rescue & approve, from the midst of 150 spam comments which are plaguing my blog at present. I’ll let other Czech speakers and language experts respond to your points as I’ve already had my say. But I enjoyed your last comment, picking up a grammatical error in the Czech on the poster. This just confirms what I’ve been told by a number of Czechs concerned for the purity of their language, that many other Czechs very badly misuse their own language 🙂

And I’ll be contrary and say the “od” phrase is better than the one without it. “Až p?jdu p?es most Karla do Divadla národa na St?nu ?erta, pak uznám, že jste vyhráli. Ale bude to vít?zství Pyrrha (d?íve Pyrrhovo vít?zství)”.

In other words, it may be redundant, but it sounds much better, and also more persuasive (which plays an important role on a poster). It’s something like “Personally signed by J.K. Rowling”. Of course “personally” is obvious – but it sounds nicer put that way!

Oops, I forgot about the diacritics! “Az pujdu pres Most Karla do divadla národa na Stenu certa, pak uznám, že jste vyhráli. ale bude to vítezství Pyrrha (drive Parrhovo vitezstvi)” – which, for you non-Czech people, is a quote from the Smoljak-Sverák film “Nejistá sezona”.

Hana – you are allowed to contradict your fellow Czech 🙂 And thank you for understanding the technical problem of some diacritics appearing as ‘?’ by re-posting your quotation in the next comment.

Hi Ricky, this is a very thoughtful and interesting post and I appreciate you bringing it up. My brother watched a lot of the Olympics on Czech TV and was really irritated by the adding of -ova to non-Czech athletes as well as not enough coverage of British success! But I did understand his dissatisfaction with CT as it does seem unnatural adding ova to someone who isn’t Czech. Everyone should be entitled to be called by their proper name in all languages. Similarly, you should be entitled to your name in your language. So if you’re called Pierre or Pavel you shouldn’t feel you need to change it for English speakers, unless you want to, of course… Same would apply for less common names. My Gran always anglicises Czech people’s names which I always discourage her from doing.

My parents were married in Prague and their Czech marriage certificate has my mum’s married name as Roeova which, to me, sounds completely unnatural. I understand the importance of Czech grammar but it does seem like the ova and a western surname creates needless confusion. So, I’m pleased this new law prevents the combination of Western surnames with Czech grammar in marriages, should that be the desired outcome 🙂

Hi Russell, and thank you for adding your comment to this interesting debate.

I very much agree with your statement that, “Everyone should be entitled to be called by their proper name in all languages”. Adding ‘ová’ to the surname of someone who is not Czech, sounds absurd, as in the example of the Olympic Games, and is misleading & inconsiderate as far as I am concerned. As I point out at the end of the post, no one writing in English about Petra Kvitová, would ever think to change her name to Petra Kvita.

I also agree with you about not anglicising a Czech person’s Christian or first name. Some Czechs will tell you what the English equivalent is, most of which I know by now owing to the limited number of Czech first names that are officially allowed 🙂 But I always try & use the Czech version when speaking to them because that is their correct name.

Adding ‘ová’ to your father’s surname does create a very interesting situation, as it results in three successive vowels, something unheard of in Czech 🙂 It is much more common for several consonants to be put together to form a Czech word, a concept beyond the comprehension of most English-speakers. The change in the law has come since your parent’s marriage & I suspect your mother will not be allowed to change her official Czech surname retrospectively.

“As I point out at the end of the post, no one writing in English about Petra Kvitová, would ever think to change her name to Petra Kvita.”

However after the Wimbledon final 2011 the English writing journalists changed her father’s name to Jiri Kvitova:

Jiri Kvitova was every bit the proud parent as daughter Petra took the spoils. 🙂

Oh dear, bibax – I wasn’t aware that some journalists writing in English, had made that mistake. But a little bit of internet research confirms that the British ‘Daily Telegraph’ was one of the offenders. Basically, I would regard that as poor journalism, especially from a specialist tennis correspondent.

“I am sorry folks, but a lady with the name Kate Middletonová, does not exist.”

And what about Alzbeta II. and Jiri VI.? They never existed as well. They are merely fairy tale persons. 🙂

Yes bibax – Writing about Alzbeta II and Jiri VI instead of Elizabeth II and George VI is worse than adding ‘ová’ because there is no grammatical justification for it at all. It is the reverse of what Russell rightly, (in my opinion), criticises his grandmother for doing when she speaks about Pavel in English & insists on calling him Paul.

“Writing about Alzbeta II and Jiri VI instead of Elizabeth II and George VI is worse than adding ‘ová’ because there is no grammatical justification for it at all.”

I took the nearest book on Czech History to hand and opened at page 37 and read: “The remarkable cultural and economic flowering of Bohemia under Charles IV was the culmination of trends begun under the Premyslids…” (Hugh Agnew, The Czechs and the Lands of the Bohemian Crown, Stanford 2004)

Turning to the English language edition of A History of the Czech Lands by Panek, Tuma et al, published by Charles University in Prague, the Karolinum in 2009, I notice that on p 164 when inroducing him they use the English version George of Podebrady with the Czech version (Jiri z Podebrad) in brackets after before using the English version throughout the text.

I think using the word “worse” in your statement is OTT. It’s a naming convention used in Czech. Just like we have naming conventions in English.

I remember the first time I saw the names of the Catholic monarchs Fernando y Isabella in Spanish. Took me a second to realise they were talking about Ferdinand and Isabella.

David – you make a fair point. In English, both written & spoken, we do tend to anglicise the names of some foreign historical figures such as Charles IV. But we tend not to do it for more recent well known individuals. Does anybody speak or write about Wenceslas Havel rather than Václav Havel? Hence in reverse, I don’t think it is right to speak or write about Alzbeta II or Jirí VI.

Please forgive me but, as someone who on several past occasions, has been quick to point out my odd spelling or punctuation error, can you please explain what the word ‘inroducing’ means? 🙂

Consider the following Czech sentence:

“Merkel navštívila Clinton.”

It does not make sense in the Czech language. It can have two meanings:

– Merkelová navštívila Clintonovou (Merkel visited Clinton)

– Merkelovou navštívila Clintonová (Clinton visited Merkel)

Thank you Karel – you clearly indicate the problems of not adding ‘ová’ to the surname of non-Czech women without causing problems of understanding the correct meaning of what is being said.

“After all, when writing in English about the latest tennis match played by Petra Kvitová, no one would dream of calling her Petra Kvita.”

I remembered this sentence of yours yesterday when browsing digitized birth registers from the 19th century. In German-written registers, female names were habitually stripped of -ová.

Interesting comment Jana. Another Czech lady called Dagmar, commenting on this post on Facebook but not here, wrote ‘I saw the baptism register with women names without ‘ová’ even as late as in 1905, so it seems to be a fairly new invention’. I said in reply that I thought the reason would be, not that it is a recent invention, but rather the use of German during the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Hi Ricky

The crux of the matter would seem to be that kings and queens (and possibly extended royal families and the nobility) have different blood and are therefore treated differently by the different languages. And also the Pope. Celebrities, politicians, actors and so on are lesser mortals and enjoy no such privileges.

The Spanish, for example, always translate the names of foreign monarchs (Queen Elizabeth is La Reina Isabel, Prince Charles is El Príncipe Carlos, etc.) but would never dream of saying Juan Lennon or Pablo McCartney.

Czech would appear to follow this convention, as would English, although

English curiously translates the names of virtually all Spanish monarchs until it gets to the present one, who is left as Juan Carlos, I’m not sure why.

Hi Jonathan

Thank you as always, for your pertinent observations.

It isn’t just King Juan Carlos whose name gets left unchanged in English. I cannot think of any other current reigning monarch whose name we anglicise. The interesting exception, (though not strictly a monarch), is one you mention, which had also previously crossed my mind when answering David Hughes – the Pope. This partly arises because of different original languages. Should the Pope Emeritus be Benedikt (German spelling) or Benedict. Should the current Pope be Francisco (Spanish spelling) or Francis. Or should we use the Latin form of their adopted names? The official language of the Vatican is Latin!

My Czech wife insisted on not adding “ova” to her name when we married in the Czech Republic five years ago. It was a bit of paperwork, but not too much trouble. It would just confuse Americans…she is not a language purist.

Michael – I can fully understand the decision your wife made. You’re quite correct in saying that the Americans in particular, would be totally confused. And Czech law does now allow people like your wife, to make that choice.

I don’t get it…arguing that “Kate Middletonová” doesn’t exists is nonsense. If our mutual friend’s name was “Karel”; and if I’d like to tell you that we are having a beer together; I would say “jdeme s Karlem na pivo” … would you argue that you don’t know any “Karlem”? I know this example represents declining rather then “gender issues”:) but it sure represents that in Czech language the names get changed very often and in different ways. I don’t see why this particular “-ová” is such a big deal…

Mrak – I do understand how names do change in Czech such as in the example you give. I know that in the accusative case, I become Rickyho. But putting ‘ová’ on the end surnames of non-Czech females sounds & looks absurd. It isn’t part of their name.

What about reciprocity. Czech will respect English names and start to write Rowling and English/American will start to respect Czech/Russian names and write for example Pot??ek,Šarapová instead of Potucek and Sharapova. How is that, I think that’s fair.

Jan – you make a fair point. However, with Russian, you are transliterating from another alphabet so it is understandable that a Czech would write ‘Šarapová’ whilst an English-speaker would write ‘Sharapova’. Your other example has unfortunately suffered from a problem I’ve highlighted several times previously on this blog.For technical reasons beyond my comprehension, some Czech diacritics just do not reproduce here as they should & instead appear as ??.

OK, understood, then just consider Šarapová as a Czech name 🙂 or another typical Czech names with a lot of diacritics.

besides, considered reciprocity, why to even Russian name transliterated into Latin? let them in theirs original Cyrillic form 🙂 Russian would be very happy.

The similar problem we can see on some English pages reporting, for example, about Bed?ich Smetana, Antonín Dvo?ák, often written Bedrich Smetana, Antonin Dvorak, without diacritics.

Dear Ricky,

I am completely mesmerised by this discussion! For me as a Czech student of English language and literature this topic is really an interesting one. Even though I have my doubts about adding the suffix -ová to foreign names, I’ll try to explain why it is so commonly done.

Czech is an inflectional language with a very free word order. What helps us to find out the meaning are inflectional endings – without these the sentences would often not make sense. Even when we use foreign male surnames, we tend to add inflectional endings when possible (it reminds me a funny case of Mr. Smith that can have two different declinations – influenced either by the written or the pronounced form of the surname), but it is not possible with female surnames. That’s why we add -ová – so we can decline this part of the surname. As long as we invent a new “vzor” for declining female surnames without -ová suffix, the problem won’t be solved.

But still I can imagine that Czech sentences could work with non-declinable names and surnames, people would get used to it. But that’s the problem – majority of the Czech population is used to adding -ová suffixes to all foreign names and it is very difficult to get rid off this habit even when you want to. And some people do not.

Anyway, as our Ústav pro jazyk ?eský is considering applying some new rules and innovating Czech, it is possible that one day there will be rule forbidding to add -ová suffix to foreign female surnames :-).

Lucie – thank you for leaving this detailed and interesting comment. The fact that Czech is an inflectional language is one that some previous commenters have also made. But it does seem absurd to anyone who isn’t Czech, to hear ‘ová’ being added to a non-Czech female surname, especially when the name is just being listed, such as in the example I gave of the finalists in an Olympic race.

Yes – languages do change & I think, despite the vocal disagreement of some Czech purists, this is one change that will have to happen.

Ricky,

Great blog, lot of interesting observations as well as some of your valuable thoughts (if some of them are bit provocative – even better as it usually triggers very interesting discussion!).

I am Polish working as expat in Czech Republic and just wanted to add my view (and Polish experience concerning same matters) after going through the whole interesting thread.

Polish and Czech languages are both part of the same West Slavic group and they are relatively similar in terms of both vocabulary as well as grammar (with some significant differences though). What happened in Polish, we somehow dropped “ova” (or rather “owa” as v letter does not exists in Polish) suffix for very significant part of our surnames, which are not typically Polish (or rather do not originate from places of origin, like most “classical” Polish surnames). Historically, we have been adding “owa” suffix for wife, as well as “ówna” suffix for daughters… so even more complex! It has been abandoned some time before the war, however older generation sometimes still tends to use it.. for example my grandmother whose name is “Egid” still introduces herself as “Egidowa” and when my mother was very young she was told to present herself as “Egidówna”. As I said – it is already completely extinct and nobody follows such rule nowadays. However – situation is different for the most classical Polish surnames which end with “ski” or “cki”. They historically belonged to the Polish gentry and those surnames originated from the name of the places – towns or villages where particular family was living in the past (for example Kwasniewski – originates from Kwa?nice town, Komorowski – Komorów, Petelicki – Petelice etcetera). For those surnames we still follow strict distinction for male form (Kwa?niewski, Komorowski) and female one (Kwa?niewska, Komorowska) as it is pure rule of the Slavic grammar (basically same rule applies as in case of the adjectives) and it simply can not be changed without amending some very basic structural rules of the language.

The argument that it might be considered as bit offensive due to it’s roots does not really convince me… It is simply fact of life that not only language but also some other social rules of our societies have been greatly impacted by the fact that historically we have been living in patriarchal communities. When it comes to the language, I believe there is nothing wrong in it – it is just historical legacy, no way to deny it and if anyone would be really keen to change it – possibly we would need to go very deep and completely re-design some basic foundations of our languages in terms of grammar and vocabulary.

One point I tend to agree – it does not make much sense to force applying same rules to not Slavic names (even if it sounds not proper for the locals), but I guess it is just sign of our times… World becomes global village and I guess every language needs to adopt to the new environment to the certain degree(in this case – very common use of foreign names, which was not the case in the past). We are facing similar issues in Polish, where – for instance – officially there are no “V” or “X” letters in the Polish variation of Latin alphabet, which was not the problem in the past as there are simply no Polish words containing those letters, but these days due to the massive flow of the foreign words and terms, it is kind of challenge for the language… just one example: we say “Ksero” or “Linuks” by replacing “X” with “KS” in most cases… Very weird (even for local people), but that’s how it is. 🙂

Michal – thank you, both for your compliments about my blog, and also for this detailed & fascinating comment.

I was well aware of the connection between the Czech and Polish languages & that different endings for the surnames of males & females, is or was, a common trait of many Slavic languages. See my earlier reply to Lis Sowerbutts about the Russian brother & sister living in New Zealand.

My main point, and one with which you also seem to agree, is not imposing a feminine ending on the surname of a woman who is not of Slavic origin, especially when her name is just listed, such as on a book cover, or as a contestant in an Olympic race.

I particularly enjoyed your last paragraph about how Polish tries to cope with foreign words which contain letters that are not normally part of the Polish language. As I have frequently commented here & on Facebook, when an English word is adopted into Czech, it always appears very amusing to native English-speakers when these words are made plural in the Czech manner by adding the letter ‘y’. Seeing ‘snowboardy’, ‘skateboardy’, ‘hot dogy’ etc is hilarious 🙂

Some of the newest thoughts on this issue:

http://www.expats.cz/prague/article/for-moms/whats-in-a-name/

Hi Sarka – many thanks for the link, on which I’ve now left a comment linking back to this post 🙂