Right from the beginning of my time spent living and working in the Czech Republic, one of the things that has constantly amused me, is seeing an English word on a shop, an advertising hoarding, or in a menu, with the letter ‘y’ added to the end of the word. For example – a sports shop advertising that it sells ‘Snowboardy’ and ‘Skateboardy’.

There is a simple explanation as to why this occurs – adding the letter ‘y’ to the end of a noun, is the most common way in Czech, to make a word plural. It is the virtual equivalent of adding the letter ‘s’ in English, so that ‘snowboard’, becomes ‘snowboards’.

However, very few of even the most fluent English-speaking Czechs, understand why ‘snowboardy’ and ‘skateboardy’ seem so funny to a native English-speaker. But the reason is because, adding the letter ‘y’, is the way the diminutive is made in colloquial English. For example, ‘John’ becomes ‘little Johnny’. In fact it is more common, for the diminutive to be made by adding ‘ie’, with ‘James’ becoming ‘little Jamie’ But the way both ‘y’ and ‘ie’ are pronounced, when added to a noun, is exactly the same.

Some of the earliest examples I observed are above supermarket shelves which offer ‘Snacky’ and ‘Chipsy’. This second example I find particularly amusing. Czechs have adopted the American English ‘chips’, for what in British English, would be called ‘crisps’. Yet despite already being plural, because of the letter ‘s’, they still go ahead and add the letter ‘y’ 🙂

Similar examples can be found in bookshops. There will be section headed ‘Thrillery’ and nearby, another section headed ‘Detektivky’. This second example does include a slight change from the English spelling, but the origin of the word is still obvious.

Other examples I’ve come across include, for feminine hygiene purposes, you require ‘tampóny’. And in the male toilets of some bars, you will find a machine from which you can purchase ‘kondomy’ 🙂

Until recently, my favourite example has been the one featured in the photograph at the beginning of this post – ‘hot dogy’. I saw it first, over four years ago, when stopping at a service area on the Prague-Dresden motorway. Sadly, when I last called in there, some months ago, the sign had gone, during the redevelopment of the venue. But in similar fashion, I have also seen signs for ‘fast foody’, but not yet captured them on camera.

The example in this photograph is the hot drinks menu in one of our local bar restaurants. It is amusing because of featuring ‘drinky’ 🙂 But as any Czech language purist would tell you, there is actually no need for it. There is a perfectly good existing Czech word for ‘drinks’ – ‘nápoje’. But in this venue, popular with students from the nearby Technical University, the English word is preferred – but made plural the Czech way!

I am always on the lookout for fresh examples to bring a smile to my face. In recent months, I’ve seen more than one conference offering, as part of their programme – ‘workshopy’. And I gather it it possible to go shopping in a number of edge of town ‘hypermarkety’.

However, my current favourite, I spotted (appropriate description 🙂 ), in an advert on a tram, a few weeks ago. Last Sunday morning, it was the tram on which I travelled from the Chaplaincy Flat to Church, and so I got a photo. A wi-fi provider is offering the possibility of several ‘hotspoty’ 😀

Y oh Y Ricky?,

Just think how outlandish it would be to see drinksy to go with your chipsy. Do you foresee having to become known as ‘Rick’ to your Czech speaking friends and remaining ‘Ricky’ to everyone else? You’ve probably seen much the same convoluted procedure on your visits to Poland with the addition of ‘owy’ or ‘wy’ to English words especially tech terms like Electronicsowy and Computerowy. Enjoy it! Sean.

I do enjoy it, Sean – hence this post. Adding ‘y’ to make a noun plural is a perfectly understandable rule in the Czech language. But it produces the results I illustrate in the post which appear so funny to native English-speakers.

Regarding my name, I always say that it’s very Czech, as it is my diminutive, being formed from the end of my actual first name, ‘Warwick’. Every Czech tends to be known by a diminutive version of their actual first name, when being spoken with in informal Czech.

I like your similar examples from Polish. However, surprisingly there is a widely used Czech word for computer – pocítac – rather than komputer & then komputery 🙂 And for Czech speakers, I do know that there should be a hácek over both ‘c’ in ‘pocítac’, as there should be over the ‘c’ in ‘hácek’, but the text used on this blog will not allow it 🙁

Language is indeed funnY. I love all these examples you have brought us, Ricky. When Americans comes to Sweden, they get confused by some of our words and the one they enjoy the most is the word for entrance and exit, the ones that are used when you enter or leave f.i a highway. In Swedish they are called utfart and infart, causing serious giggles and numerous selfies by the traffic signs…..

In Sweden that Y is not used for any particular purpose, but men with a name ending with a Y, Johnny, Conny, Tommy, Billy , Benny, are mostly born in the late fifties or early sixties and are considered, for reasons unknown, to be the somewhat bad and unreliable fellows, boys a girl should be cautious with when dating. In Sweden, that is, Ricky, in the UK things are of course entirely different!!!! In Czech environment, you should be doing great. Thank you for this amusing post!!!!

Language is indeed funny, Solveig, hence this post. I’m glad you enjoyed my examples. And I can completely understand why some Americans would find ‘utfart’ and ‘infart’ amusing. Many British people would do also.

I’ve never had a problem here in the Czech Republic, with my first name ending with the letter ‘y’. However, my surname beginning with ‘Y’ can be an issue as no Czech surname begins with ‘Y’. There is therefore no storage slot at the Post Office for packages that won’t fit in my mail box which I have to go & collect. Usually, they’ve been stored under ‘J’ because that’s the way in Czech to pronounce my surname – Jates 🙂

Czech bashing again? As an English native speaker who works as a teacher here I fail to see the hilarious side of it. It’s their language and it’s part of their grammar. It’s often English speaking people who travel the world and are often seen to ridicule others for their language, custons, traditions. As English is the international language, they come with the mentality that others should conform to them. They often fail to learn another language because, after all, everyone should speak English. Nice to see you’re easily amused at the expense of another ones language, customs, etc. I would have thought that someone in your position would be more tolerant.

Matthew – No, I am not ‘Czech bashing’ as you put it. I am neither making fun of the Czech language nor the Czech people who speak it. In the second paragraph of my post, I clearly state that, ‘adding the letter ‘y’ to the end of a noun, is the most common way in Czech, to make a word plural’. I am not making fun of that fact, it is a rule of Czech grammar as you likewise say. As I also state, “It is the virtual equivalent of adding the letter ‘s’ in English, so that ‘snowboard’, becomes ‘snowboards’ “.

What I am doing in the blog post, is pointing out that to most native English-speakers, though obviously not to you, when an English word has been adopted into Czech, adding the letter ‘y’ to it to make it plural, sounds funny because it sounds as though the diminutive is being made. I am fully aware that what is happening is that a rule of Czech grammar is being followed. But I fail to see what the problem is in smiling about the consequence.

As my previous commentator says, (a female Swedish Lutheran priest writing in her second language English), ‘language is indeed funny’. She can clearly see that when some American visitors to Sweden see ‘utfart’ and ‘infart’, it causes serious giggles. She doesn’t get offended. It was a fluent English-speaking Czech friend of mine, who does see why adding ‘y’ seems funny to native English-speakers, who pointed out ‘fast foody’ to me, before I saw it myself.

It is indeed funny to the untrained English-speaking eye! I enjoy Czech diminutives in general – my favorite is hol?i?ka (baby girl), the diminutive of holka (little girl). We hear it a lot because that’s what people call our dog 🙂

Likewise, my Czech students have gotten a kick out of us adding “mini-” to things to make them diminutive in English.

And don’t get me started on idioms from each of our languages! Great post.

Glad to know that you can see the funny side of this, Emily. Like you, I enjoy hearing & usually understanding 🙂 Czech diminutives – thank you for your example ‘holcicka’, though I cannot put a hácek over either ‘c’ in the word because my blog set-up doesn’t cope with some Czech diacritics 🙁

How interesting that your Czech students enjoy the way we add ‘mini’ to certain nouns to make the diminutive in English. The origin of doing this only goes back to the 1960s, first with the Morris Mini-Minor car and then with the mini-skirt. With these two examples, it is no longer necessary to add the noun as, ‘He’s driving a mini’ and ‘She’s wearing a mini’ are both perfectly, easily understood.

As for idioms, my favourite example of the variation between languages is the English, ‘having green fingers’, to indicate someone is good with plants &/or gardening, which in German is ‘having a green thumb’.

I remember thinking it was so funny at first too, before I knew what it meant. It is amusing for me to see Czech-ified English too, verbs like facebookovat, DJovat, etc. My Czech teacher hates it when I try to English-ify things because I forget the word, but I know that they are used in Czech language, so what can she do 😉

Hi Cynthia – I think many native English-speakers, when they first see English nouns with the addition of the letter ‘y’, think it is funny because of the way it sounds and what it implies in colloquial English. But if you seek to learn Czech, you soon realise there is a perfectly good grammatical reason for it.

Like you, I too smile when I hear what you describe as ‘Czech-ified English’. When walking around our local Kaufland supermarket, there are advertising announcements saying what special offers are available ‘u Kauflandu’ because of it being the locative case. Likewise, if you are on Facebook, it is ‘na Facebooku’ for the same grammatical reason.

I think your Czech teacher is what I would call a Czech language purist, who would object to ‘drinky’ and insist on ‘nápoje’ 🙂

Hi Ricky

My favourite Czech word is “pizz”, which I saw on a street advertisement the other day. It’s the feminine genitive plural form of “pizza”, which faithfully observes the “zena” form.

By way of contrast, all words borrowed from English appear to be regarded as masculine, presumably because the cases are more “naturally” constructed in that gender.

Loan words (usually from English) are sadly inevitable in a global world with a great dependence on technology, so some of the examples you mention are understandable, but it’s a bit annoying when Czechs use loan words when there’s a perfectly good Czech equivalent (I think “drinky” is most often used for fancy cocktails and things rather than drinks in general).

By the way, I may be wrong, but I think “u kauflandu” is actually genitive, not locative. “u” vaguely translates as “at/by”, which is why 99% of Czechs say “I spent the weekend by my grandmother’s” (“u babicky”) instead of “at”.

Hi Jonathan,

Thank you for once more commenting here. I do like your new favourite Czech word ‘pizz’ and especially your grammatical explanation of how it comes about 🙂

I certainly didn’t know that all words borrowed from English appear to be regarded as masculine in Czech and thank you once more for your presumed grammatical explanation.

I agree with you that in a global world, especially in the area of technology, loan words from English are inevitable. But as I said in response to the comment by Sean, surprisingly in Czech you don’t have ‘Komputer’ or the plural ‘Komputery’. Likewise I agree with you, that when a perfectly good word for something already exists in Czech, you don’t need an English loan word.

With regard to your last paragraph, I’m sure you may well be right. However, if I am wrong, I’m surprised that an English-speaking Czech hasn’t yet commented, pointing out my incorrect case, as has happened previously here on my blog.

Ricky: After reading your post and the comments, I must relate some of what I did when I worked in the Czech Republic in the late 90″s. I was working in the Czech Academy as a research chemist. When the Czech scientists in the department heard that an American was in the building, I received numerous requests to review scientific manuscripts to “polish”. The authors wanted me to convert “Czenglish” to proper English grammar. The Czech scientist almost always publish their work in Czech and English.They know that their work will not receive wide readership if they only publish in Czech, while at the same time they want their fellow Czech scientists who are not fluent in English to be able to read their work. The most amusing part of all this is the fact that I am very poor in English grammar, so I was forced to consult my wife Elaine (who is a crackerjack English grammarist) for help.

Bob – Thank you for once more visiting & commenting.

I can completely understand as to why Czech scientists would want their work published in both Czech & English for exactly the reasons you outline. But I’m pleased that many of these, no doubt, very capable scientists, were aware that their written English was not necessarily of a standard for academic publishing & sought your help as a native speaker. Very pleased that you, with Elaine’s grammatical input, were able to help out.

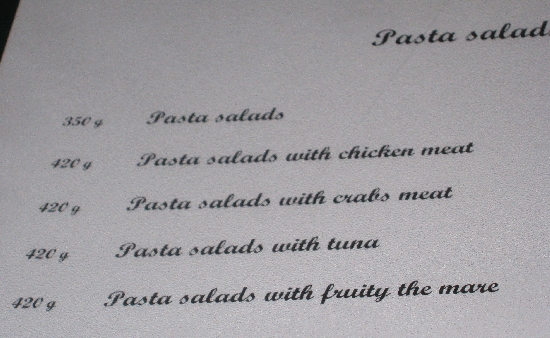

Sadly, in my experience, there are many Czechs who can speak reasonable English & thus think that they can write it too. I’ve seen the resultant Czenglish in everything from menus to beautifully printed colour books. Whenever I need something put into Czech, I always consult a native Czech speaker, to avoid doing exactly the same in reverse.

Word “drinky” is used in slightly different sense than “nápoje”, drinks in Czech sense are mostly some either chemical wonders of modern age, or something more noble, or younger people are using it to emphasize glamour of situation in which they are consumed.

“Napij se” can say your mother, “dej si drink” can say man of big world, close to James Bond.

Thank you Pavel, for this explanation. As a native Czech speaker, you’ve confirmed the suggestion made by Jonathan in an earlier comment. I’m most grateful.