I’ve written many times previously about this strange language that I regularly encounter in the Czech Republic which I call Czenglish. I’ve found it on menus, on market stalls, on buildings and on public notices. If you want to see other examples besides those I’ve just linked to, put ‘Czenglish’ into the search box on the top right-hand-side of this page and hit ‘enter’.

On the left is my latest example of this strange language. The Kulat’ák Restaurant here in Praha 6, is proud to offer an exclusive French female cousin to its customers. For the benefit of the proprietors of Kulat’ák, it should be ‘Exclusive Cuisine’.

And when correcting this hilarious mistake, the first statement also needs to be amended to read ‘The first Pilsner Urquell Original Restaurant’, both to correct the grammar to acknowledge that there are now other restaurants based on this concept which have since opened in Prague. In the third statement, the word ‘offer’ needs to be corrected to the plural – ‘offers’. And the last statement should read ‘Award-winning tank beer’.

The sign in my photo is of one of several identical ones that the proprietors of Kulat’ák have had made to display around the area nearby, in order to attract customers to their restaurant. They are quite substantial and no doubt each cost a considerable amount of money to be manufactured. And yet no one could be bothered to actually ensure that the English text was accurate and made sense. I just cannot understand the thinking – or lack of it – that lies behind such a decision. However, following a conversation that Sybille had a few months ago with one of the joint owners of U Topolu, a bar-restaurant that we quite regularly frequent, it finally dawned on me why so much Czenglish abounds.

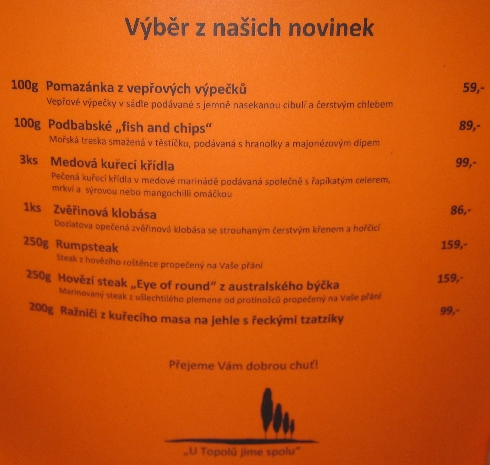

U Topolu only has one copy of its menu in English as, being situated in the suburbs, it isn’t visited that often by non-Czech speakers. And to be fair, the English in the menu is relatively error free except for a few incorrect prepositions and the suggestion that you enquire as to the ‘desert of the day’. But because of the relative proximity of the Crown Plaza Hotel, which frequently has numerous German tourists staying there, on occasions a few of them are slightly more adventurous and patronise U Topolu.

Sybille therefore kindly offered to the joint owner, that if he would like to have a copy of his menu translated into German, she as a native speaker, would be happy to do it for him. His response was a real eye-opener. If he wanted his menu in German then he could do it himself because he could perfectly well make himself understood in German.

What this gentleman articulated is the mindset of almost all Czech people who have ever travelled beyond the borders of their own country. Czech is a minority language – I hope Czech people will forgive me saying so. Other than 10 million fellow Czechs together with 5 million Slovaks, nobody else understands Czech. Therefore as a Czech, if you are going to communicate outside of your own country, you have to make yourself understood in another language – usually English or German.

With the exception of a few hotels and resorts in the Greek islands that specifically set out to cater for Czech and Slovak tourists and consequently employ some Czech or Slovak staff who can then write the menu in Czech or Slovak, nowhere else would a Czech person find, or expect to find, a menu in their native language. Instead, Czech people have to have at least a limited capability in another well-known language, most commonly English, or if in Germany, Austria or Switzerland – German. Therefore they never see a menu or notice written in badly constructed Czech because nobody ever sees the need to translate anything into Czech in the first place!

Because since the Velvet Revolution, many Czech people have travelled abroad and succeeded in making themselves understood in English when ordering a meal or booking a hotel room, they therefore believe that their English is sufficiently good to translate a menu or compile a notice. But as all my examples clearly show – it isn’t! Part of the problem is that Czech people can usually speak English far better than they can write it. Hence ‘desert’ rather than ‘dessert’; ‘sunrice’ rather than ‘sunrise’ and ‘hallowed’ rather than ‘hollowed’.

Am I correct in my analysis? I’d love to hear from both expats and Czechs. And I do promise that this is the last time I will write about Czenglish – that is until I see the next example that leaves me creased up with laughter!

Well I am a native English speaker from the United Kingdom, and as you know I have enough difficulty with English as it is, never mind trying to correct the Czechs 🙂

It is quite funny about all this Czenglish business though, especially when one thinks of how easy it could be to get a proper translation done. 🙂

Hi Ricky,

The last line should be Certified Tank Beer – there is nothing in the Czech about any award having been given. The issue is of course that it is unpasteurised and is kept cold in a special type of tank rather than the usual kegs (these sterile containers avoid any contact with the air, but the containers are polypropylene). Some specialists claim it is higher quality beer, but I think it is only a marketing ploy (OK, kegs can get warm, but any place selling 4-5 hectoliters of beer a day /the requirement to get a tank from the brewery/ probably had the kegs stored properly – they were tapping a new keg daily anyway).

The line above that is also ‘mixed’ – the Czech ‘domestic’ becames ‘traditional’ ingredients. My guess is they tried to market to their audience and missed the mark.

Spending a lot of money on signs made sense to the owner, but spending a bit of money on translation did not make sense: ‘ah, it’s close enough’. This is where awareness of the expectation of the audience is lacking. What would be ‘close enough’ for the Czech audience may not suffice for other nationalities. My favourite example of this kind of national ‘chauvinism’ (not to be confused with male chauvinism) is Prague Castle – asked to send a representative statue to Japan for an exhibition on the Czech Lands, it sent St George (killing the dragon). Cultural sensitivity? Not on your life. Of course, the Japanese were taken aback and George was sent back (how could they have that as the centrepiece of the exhibition?). Another of these national chauvinisms is putting -ova on female names (admittedly no longer required for foreign residents on official documents) or all of the exonyms in Czech (http://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seznam_%C4%8Desk%C3%BDch_exonym).

I usually put it down to lack of refinement in their marketing rather than sloppiness, but I think lack of attention to detail is also a common problem here (lack of follow-up, not checking to make sure it was done properly – literally, Did anyone sign off on the final copy before it was printed on all these signs? My guess is they have no step like that /final copy? What’s that?/. They put together the ‘copy’ and sent it to be printed. The printer puts whatever the customer sends – no double-check there either. And here we have the fruit of that collective ‘effort’).

Companies with an ISO would not have a sign like that.

All the best,

Sean

Hi Ricky,

Ads lacking a spell-check do not shock me anymore but infallibly make me angry, just as restaurant menus offering “soaps” instead of “soups”. The notion of being close enough to the target language, as demonstrated by the U Topolu restaurant owner speaks – I fear – for the majority of those in various areas of business who would never think of wasting money on proofreading (of the original text or the translation) or on translation itself, because “they know English well enough to do the job themselves and everybody will understand, right?” Apparently customers who will refuse to buy a certain product because there are mistakes in the ads, to deal with a business partner because his information material does not make sense, to continue reading an article because of the grammar mistakes, or to go to the restaurant because of its dilettantish spelling in the menu are a minority… and bound to remain one. (Btw: I am Czech, mostly considered a lunatic word-splitter by the majority society as far as languages and their correct usage are concerned.)

Wandering Pilgrim – What you say in the last sentence of your comment is precisely my point. Ask a native English-speaker to check that the English makes sense!

Sean – Thank you for correcting me about the last line & for all the rest of your detailed comment. I do find the attitude, ‘ah, it’s close enough’ very sad. Maybe I’m too much of a stickler for accuracy but without it, misunderstandings easily happen and people and businesses often appear laughable.

KX – welcome to the blog & thank you for your comment. It is nice to have another English-speaking Czech person reading it & agreeing with me about the points I raise regarding the frequency of Czenglish and how it could be easily avoided. You are in good company – some people think I’m too pernickety when it comes to spelling and writing in English!

Hi Ricky, I am native Czech 🙂 The problem with translations lies in one special thing. Many people in our country think that they can speak / write really good in English. And when your boss asks do you speak well English and you say yes, he tells you: so translate our menu into English.

Now you cannot refuse so you take dictionary and friends who also “can speak / write good English” and you see results everywhere in Prague.

To speak in English is much more easier than to write menus or other things.

BUT WE ARE WORKING HARD TO LEARN that 🙂 Sorry!!

Ondrej

Hi Ondrej – Many thanks for your comment which very much confirms so much of what I wrote in this blogpost. As you rightly say, it is far easier to speak in English & make yourself understood, than to write English that is both grammatically correct and with every word spelt the right way. Therefore, always check the text with a native speaker of English before going into print.

Hi Ricky,

Pretty good observations in your post. These days Czech can be encountered in tourists areas beyond Greece, for example in Italy, Spain and especially in Croatia where it was widely spoken between the world wars.

Yes Czech is now a very minor language but in the early middle ages it was more important than English on the continent. At least I read about it being so.That is hard to believe isn’t it?

The Czechs have a very strong opinion of themselves when it comes to their level of knowledge of foreign languages. Especially the older generation and their mastery of German. It may have been good when they were young but it has evaporated a lot with time.

Regarding English and the Czechs using it, there are two ways of thinking you can decide on. I personally subscribe to both.

On the one hand it is incomprehensible why they don’t bother to write it correctly.

On the other hand one should appreciate that they use it at all given the fact that they get more criticized for it than having their effort, howbeit feeble, acknowledged.

The English and somewhat even the German speakers are quick to make fun of someone who attempts to communicate with them in that “world” language and doesn’t do so perfectly.

This is an arrogance that one doesn’t find in Greece or even Japan when using their language. They are extremely happy at seeing the attempt and they heap praises on such person’s skills.

While it is obvious to the foreign language speaker in such cases that the praises aren’t entirely deserved, it makes them feel good and encouraged to continue studying the language.

Since you have been living in Prague for several years now, how are your Czech language skills coming along?

Cheers,

Vance

Hi Vance – Thanks for your comment.

I would never make fun of a Czech trying to communicate by speaking in English or German. Instead, I would appreciate their effort. Many Czechs express appreciation of my attempts to communicate using Czech which, to answer your question, is still very limited despite having lived here for three years. My point in this post and my earlier ones about Czenglish, is that if as a business person, you are going to spend money on printing menus or manufacturing signs, why does no one bother with getting a native English-speaker to go through the proposed text to check that it will make sense to the very people you are trying to market your business to?

I am about to have some new business cards printed. Following the example of several other English-speaking expats here, I’ve decided to have them in English on one side and Czech on the other. Just to show that I do practise what I preach, yesterday I sent my proposed text to a Czech lawyer friend who also speaks fluent English, asking him to check & correct my Czech version before printing. Even with the simple text of a business card, I’d made a couple of mistakes which he has now corrected.

Ricky, It’s very easy to make mistakes. To be pernickety I could point out it is spelt as I have written it and not as you have. Also, the verb is ‘practise’ and not ‘practice’. And Sean might like to note that ‘chauvinism’ is spelt thus.

In your defence – or as the spellchecker is trying to tell me – ‘defense’ you are handicapped by the Americanisation (Americanization) of the English language by computer.

I do enjoy your blog very much and I shall try not to be so persnickety in future – beat the spellchecker with that one.

Tim

Tim – Thank for being both pernickety (British English) and persnickety (American English) regarding my spelling when replying to earlier comments above. I have now corrected my errors as well as Sean’s spelling of ‘chauvinism’. Therefore, when anyone now reads your comment, they won’t see what you were talking about!

I’m not at all adverse to have errors of fact, grammar or spelling pointed out to me. Whilst I do take considerable care & time to try and get things right, I still do make mistakes. However, I don’t normally make corrections to the comments left by other people unless I spot an obvious transposition of two letters or a word missed out.

I’m glad you enjoy the blog. Please keep visiting & commenting.