On the afternoon of Holy Saturday, I was one of five members of the St. Clement’s congregation, who went on a mini pilgrimage. We met at Ládví metro station in the north-eastern Prague suburbs, and from there took the bus further out to Dáblice from where we began our pilgrimage walk.

Dáblice is a village which now adjoins the Prague conurbation. We climbed from the village centre, up onto Dáblický háj, a beautiful area of heathland and woods. At the top of the hill is an observatory and adjacent to it on a rocky outcrop, a cross.

From this point, there are wonderful views out across the northern Bohemian countryside.

There followed a very pleasant walk through the woods along the top of the ridge before our path took us down to the main road that runs along the southern edge of the heath. Across the main road, lay the goal of our pilgrimage – a memorial to those who resisted fascism.

The memorial is situated on the northern extremity of what was once a military shooting range, created back in 1890. During the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, the whole area was isolated and surrounded by barbed wire fencing.

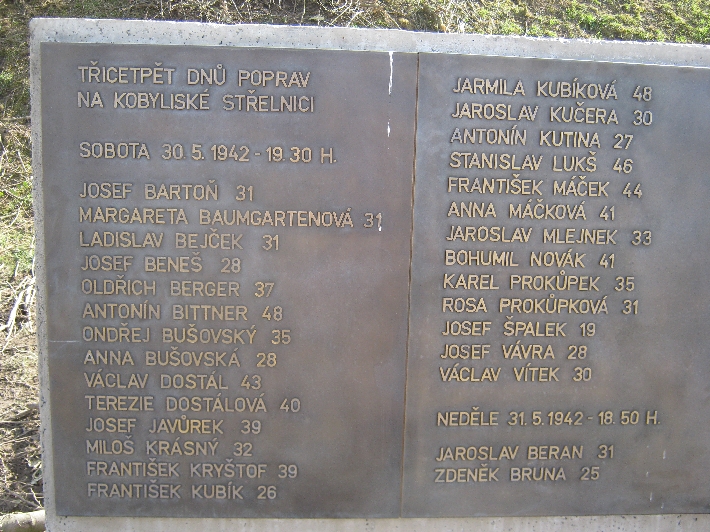

After the assassination attempt on 27th May 1942, by Czechoslovak parachutists, on Reinhard Heydrich, the acting Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, 463 men and 76 women were executed here within 33 days, including outstanding scientists, artists, politicians, soldiers, and four representatives of the Czech Orthodox Church who had provided asylum to the Czechoslovak parachutists in the Orthodox St`s Cyril & Methodius Cathedral. In total, it is believed that over 750 people were executed here during the years of Nazi occupation.

When we arrived at the memorial, we discovered that it is officially closed from March – September 2015, whilst work is carried, with the benefit of an EU grant, to renovate the site. Fortunately, it was fairly easy to get around the metal barrier across the entrance and being a holiday weekend, nobody was working there. It will obviously look nicer when the landscaping work is completed.

The names of the first people executed here, starting just three days after the Heydrich assassination attempt.

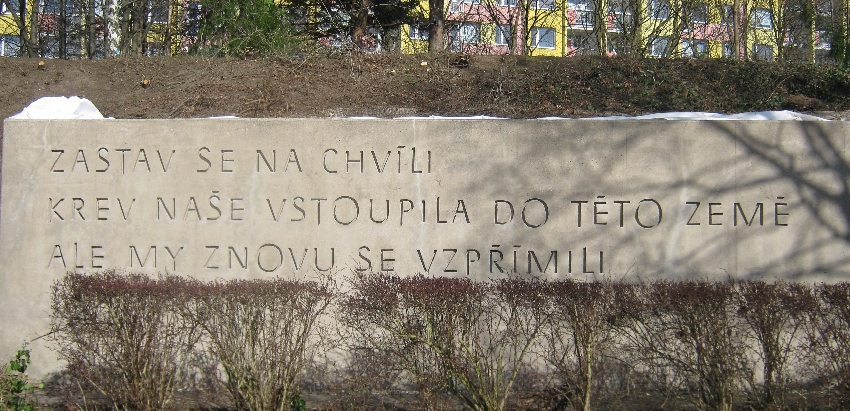

Quite clearly a new concrete wall has recently been created as part of the renovation work, to which the plaques with the names of all those executed, have been reattached.

In translation, the inscription reads: ‘Stop for a while …… our blood entered this soil but we have arisen again’.

A new cross with a crown of thorns has been erected, quite appropriate for our Holy Saturday visit.