Kralupy nad Vltavou is a city with a population of around 20,000, situated on the Vltava river, sixteen kilometres north of Prague. On 22nd March 1945, it was subject to a devastating bombing attack by USAF planes. The two reasons given for the attack were the presence of an important oil refinery and the city being a key railway hub. The aim was to disrupt the ongoing Nazi war effort.

The first wave of bombers successfully hit the refinery, setting an oil storage tank on fire, from which erupted a very large cloud of thick black smoke. This left the follow-up wave of bombers with very poor visibility to see their targets. As a result, further bombs were dropped fairly randomly, hitting residential areas of the city.

Of the 1,884 buildings in the city at that time, 117 were completely destroyed and another 993 were seriously damaged. 248 people lost their lives in the immediate aftermath of the bombing of whom 145 were Czechs. The remaining victims were mainly German soldiers. The devastation was so great that Kralupy earned the nickname of ‘Little Dresden’. The allied bombing of Dresden, with the massive destruction of its central area including the Frauenkirche, and the death of around 25,000 people, had taken place only five weeks earlier on 13th – 14th February 1945.

In January this year, the director of the city museum in Kralupy, wrote to the director of the city museum in Dresden, with what he admitted was a somewhat unusual request. He was planning a commemorative ceremony on 22nd March to mark the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Kralupy. He wrote that since a large number of German citizens also lost their lives in those bombings, he planned that a large candle—an Easter candle—be lit for all the victims during the ceremony. He wanted the candle to be donated by a German city that had suffered a similar fate, hence his request to the city of Dresden. This would be an act of reconciliation and shared remembrance.

The director of the Dresden city museum sought the help of the Frauenkirche who arranged for the production of the requested candle. Then, just over a week before the commemorative ceremony, I got an email from Maria Noth, the Geschäftsführerin / CEO of the Stiftung, the charitable foundation that runs the Frauenkirche, asking whether I would be willing to travel to Kralupy, representing the Frauenkirche, and present the candle on their behalf. Her reasoning for doing so was because of my strong ties to the Frauenkirche, (her words, not mine), because I live in the Czech Republic, and because of originally coming from Coventry & its experience of aerial bombing.

Fortunately, I was at the Frauenkirche on Sunday 16th March, conducting my regular monthly English-language Anglican service of Evening Prayer. I was therefore able to pick up the heavily packaged candle from the vestry that evening, together with my black cassock which normally lives there, and carry them both to my car following the service, ready for onward transportation to Kralupy, on Saturday 22nd March.

At the request of the Kralupy museum director, Maria Noth sent the following message to accompany the candle, which I reproduce here in full. A Czech translation of it was printed in the programme for the Commemorative Ceremony.

‘Kralupy nad Vltavou was severely damaged on March 22, 1945 – just over a month after the City of Dresden, Germany, and the Frauenkirche, located in the heart of our city, were also devastated by Allied bombers. By commemorating the destruction of Kralupy and acknowledging the shared experiences of pain and loss in both our cities, the peace candle the Frauenkirche Dresden Foundation is dedicating to Kralupy today symbolizes the power of reconciliation and healing across nations and generations. At the same time, we remember the victims of World War II on all sides, as well as those who continue to suffer from wars in Europe and around the world today.

Furthermore, we in Dresden and Germany humbly remind ourselves that the war that led to the destruction of both Kralupy and Dresden was initiated by Germany and a dictatorial regime. The Frauenkirche in Dresden was painstakingly rebuilt between 1994 and 2005, and today it stands as a strong symbol of reconciliation, a beacon of hope, and a place where we advocate for an open and democratic society. The candle serves to unite our two cities in friendship and their shared quest for peace. It will be handed over by Reverend Ricky Yates, an Anglican priest with strong ties to the Frauenkirche in Dresden, who originally comes from Coventry – the first English city to be heavily damaged by German bombs in 1940. His presence at the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of Kralupy’s destruction delivers a message of unity, humility, and collective hope for a peaceful future.’

The Commemorative Ceremony took place in the Roman Catholic Kostel Nanebevzetí Panny Marie a sv. Václava, amazingly one of the few historic buildings not destroyed in the bombing. The ceremony began with the sounding of a siren followed by the playing and singing of ‘Kde domov muj?’, the Czech National Anthem, which I managed to sing completely 🙂 Then I was invited to light the candle, assisted by Hana Matoušková, a ninety years old survivor of the bombing.

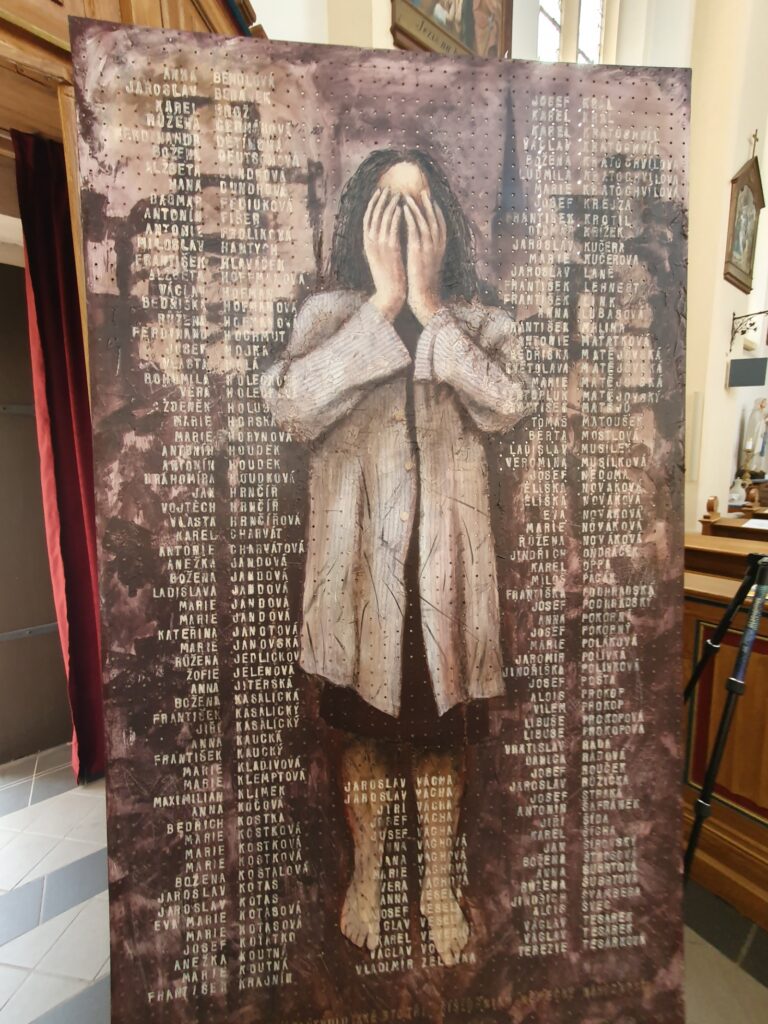

The ceremony continued with a speech from the mayor, the singing of the song ‘To Místo’, which had been especially composed for the occasion, and prayers led by the Roman Catholic Bishop of Plsen. There was a poetry reading and an interview with the artist Martin Frind, who had produced a painting entitled Rekviem/Requiem, containing all of the victims names.

For me, one of the most moving parts of the ceremony was the reading by two local teenage girls, of all the names of the victims. Several times, the same name was repeated twice and occasionally three times. Many Czech men have the same name as their father and Czech ladies, the same name as their mother. A reminder that whole families were eliminated – two, or even three generations. The reading of the names was then followed by a one minute silence.

We were then invited to go outside and lay flowers or lighted candles below the memorial on the south wall of the Church. Here, I was spoken to by numerous people either in Czech, German or English. Each one expressed their grateful thanks that I had come and participated in the ceremony and the expression of peace and reconciliation conveyed by the candle. Throughout the day, if I did have any Czech language difficulties, I was accompanied by the friendly and helpful fluent English-speaking Hana Bozdechová, the wife of the Deputy Mayor.

In conclusion, I have to say that I felt very honoured to be asked to take part in this Commemorative Ceremony, representing the Dresden Frauenkirche. On my emails, I sign myself as ‘Coordinator of English-language Anglican worship in Dresden’, because that is what I do. But it isn’t an official position at the Frauenkirche or within the EKD. Likewise in the Church of England, I function purely by holding ‘Bishop’s Permission to Officiate’ (PTO). My Archdeacon kindly says that he regards me as the Chaplain of Dresden, but I’m not, as Dresden isn’t a Chaplaincy.

However, my involvement with the life and ministry of the Frauenkirche during these past nine and a bit years, albeit in an unofficial capacity, has been extremely meaningful to me. Taking part in last Saturday’s ceremony was one additional moving experience.